Rush Hour

Performance Installation

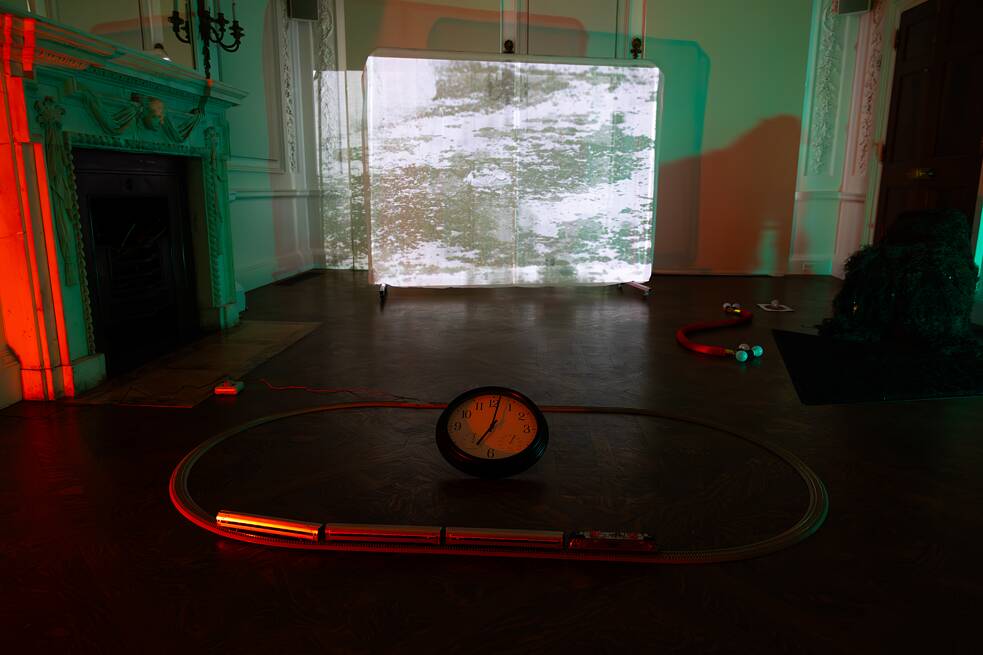

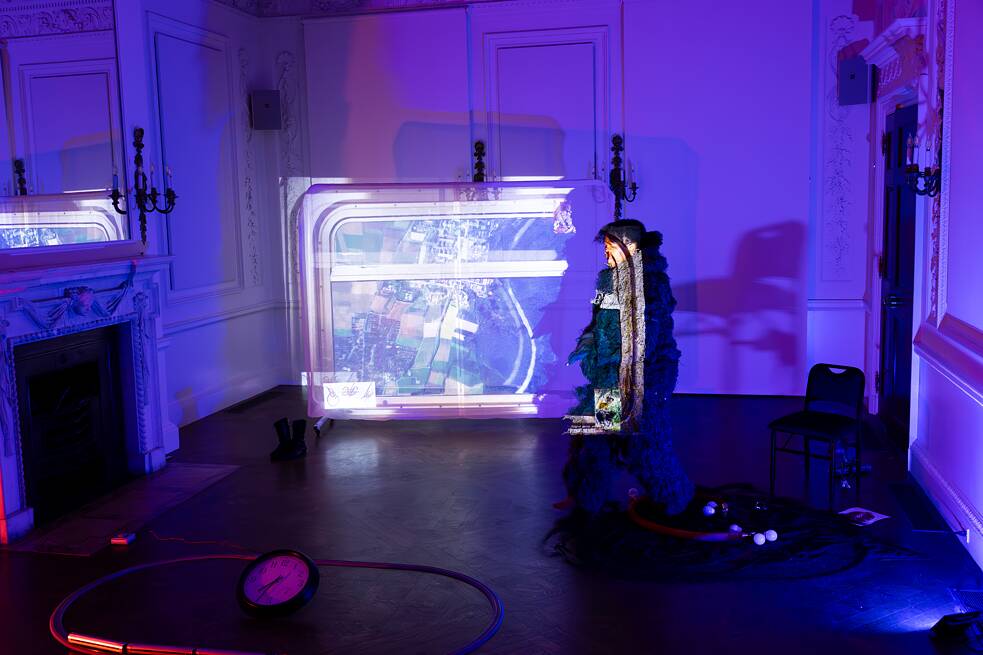

Rush Hour is a performance installation that unfolds inside a moving train as a cinematic narrative structure. From themes of migration, displacement, and time travel, it links the concept of Sankofa, a call back into history to remember, with the theory of self-reference as fertile ground for sculptural forms, spatial interventions, and movement phrases. Through a surrealist lens, the work disrupts dichotomies between body and machine, nature and industry, and stellar motion and mechanical time. Staged in three acts, Rush Hour affirms language as a care tool that shapes self-determination beyond feminine sacrifice into storytelling and dreams. The choreography and suit of objects in the work point to the cyclical nature of history. As a vehicle, the train is a liminal space that reflects the motives of colonialism, journeying to paradise for discovery as a measure of conquest. As a 2025 Studio 170 resident at the Goethe-Institut Boston, Mandeng Nken will preview Vestibule or Act 2, in which the body animates a projection of images as a fleeting, playful exercise with light, and silhouette. She will also present Act 1, Conductor, where the train's operator becomes a storyteller who combines banal observations with cosmological mysteries. Set inside and around a miniature train set, the rhythm of this section follows the repetition of a ticking clock that breaks into a glitch.

Installation, Performance and Artist Talk

Thursday, April 24, 6 PM

Pre-Interview with the Artist

1. Can you tell us about the inspiration behind Rush Hour and how you envision the train as a symbol in the piece?

Rush Hour: Unraveling Across Temporal Distortions is a choreographic sculptural study of topography through its spectral characteristics, prioritizing traces and residue as material evidence. It translates environmental research into kinetic movements to express how states of exile inscribe onto the body. The work’s central mechanism, a miniature, remote-controlled train, is the protagonist and a spectral remainder. Choreography is structured inside, around, and in response to this apparatus, following the rhythm and repetition of a ticking clock that eventually breaks into a glitch. As a guiding force, the moving train reorients and dislocates the audience within a cyclical framework that challenges the fixed temporal conditions of the historical document. The use of technology in the work produces a meditation on uncertainty and failure, to question who is allowed to retell history.

2. Sankofa plays a key role in your work. Can you explain how this concept, which looks to history for knowledge and guidance, is woven into the performance and what it represents for you?

Sankofa is an Akan principle that translates to "go back and fetch it." In the work, it becomes a call back to revisit history in order to remember. Pairing it with the concept of self reference, which relays that information is more accessible when it relates to our self, becomes a way to invoke the power of memory as a legitimizing tool. Unbound from the conditions of an inhabitable environment, memory grants us access to our ancestral knowledge systems by way of oral traditions preserved through folkloric practices. I utilize Lorna Simpson's image Waterbearer (1986) as a map key in the work for that reason. In the image, the subject carries an antiquated vessel made of steel in one hand and a plastic water gallon in another. Her back towards us, she is perpetually caught in between timelines and geographic imprints in a careful balancing act, tipping the scales one way or another. The caption of the piece reads “SHE SAW HIM DISAPPEAR BY THE RIVER. THEY ASKED HER TO TELL WHAT HAPPENED. ONLY TO DISCOUNT HER MEMORY.” The image points to how the black female subjective voice is historically discredited or erased which is a notion I use to question the recursive tempo of history.

3. In Rush Hour, language is described as a tool for self-determination. How do you approach language in your work, and how does it transport the themes you’re exploring?

In Looking for Zora (1975), Alice Walker’s search for Zora Neale Hurston’s unmarked grave confronts histories of erasure by making the spectral presence of Hurston materially visible. This symbolic crossing through geological and generational time/lines underscores the power of temporal distortion as a nonlinear mode of storytelling. This enactment of ancestral veneration frames my relationship with language as a practice always in conversation with the past, grounding an experience of a place or location I have no material access to but must reflect upon to make sense of what remained. Time is extremely plastic. I think about how spectrality mirrors a glitch, reflecting a body split across multiple timelines. In its simultaneous presence and absence, the character in Rush Hour protests a refusal against stasis, similar to the figure in Lorna Simpson's iconic image.